Sara De Bondt founded her design studio in 2004. Currently based in Ghent, Belgium, she has previously worked in London, Liverpool and Antwerp. In our extensive Studio Culture Now interview with her, Sara discusses everything from starting out at studio Foundation 33 and the influence of its founders Daniel Eatock and Sam Holhaug, to working with James Goggin (Practice), and eventually establishing her own studio and publishing company, Occasional Papers.

In this extract from the interview, Sara talks about her initial vision for the studio and how she got started, how she approaches the administrative side to her business and her working process — plus how she balances creativity and profitability.

Studio Culture Now is available to pre-order now from the Unit Editions shop. It contains in-depth interviews with 30 studio founders, advice from industry experts, alongside a fully-updated ‘Studio Intelligence’ section.

Sara De Bondt Studio, Ghent

Unit Editions: Did you have a vision of what you wanted the studio be, or an idea of the kind of work you wanted to produce? Did any designers or studios provide inspiration for structure or a way of working?

Sara De Bondt: The studio side of it just kind of crept up on me, because I had too much work and couldn’t get through it all alone. I was never interested in the infrastructure or business side of it, and have always preferred working together with people to being their boss. When I was starting out, I submitted a text for an Australian symposium about what kind of designer someone should employ — and I wrote that it should be someone who can take time to doodle or sit in the park.

I did have ideas about the kind of work I wanted to produce: honest, open, appropriate, careful, and aware of its environmental impact. Above all, I tried not to take it too seriously: even though I still spend almost all of my time thinking about it, it is only graphic design.

James [Goggin] was part of a network of recent Royal College graduates, that included Kajsa Stahl and Patrick Lacey from Åbäke, Lizzie Finn, Jonathan Hares, Laurent Benner, Frauke Stegmann, and many others…. When James and I moved to Shacklewell Lane in Dalston, we ended up in a building full of other creatives. We’d hang out for lunch and tell our visitors to see the others, too. I felt supported by that group of people.

Occasional Papers bookshelves

UE: Can you describe the process you went through to get started?

SDB: One of the first jobs that James and I did together was a pitch for Camden Arts Centre, to design their File Notes — small exhibition booklets which you can buy individually or collect in a binder. It’s something we still work on today, 15 years later. We live in different continents now but we take turns producing them. There are details by which you can tell who designed which one.

We had an inkjet and a second-hand black-and-white laser printer. James had invented a template to produce these inkjet-printed portfolio booklets, bound together with metal clips, which I copied. I had a lo-fi website that I had cobbled together in Dreamweaver and printed a business card on the side of another job. You could still get free illegal copies of design software back then instead of the overpriced subscription models of today.

UE: Did you turn to anyone, or use any resources, for advice and help? Did you have to borrow any money, or work out a business plan?

SDB: I was already working for clients on the side during my studies and at Foundation 33, which meant that I had a few jobs to get me started. When I left the studio, Dan and Sam also passed on a project they no longer wanted to be involved in. My father used to be self-employed, so I was not unfamiliar with the constant fear of having no clients. I had saved up some money beforehand, which meant that I didn’t need to borrow any from a bank — and there was no need for a business plan.

My then-boyfriend and I lived in a tiny two-bedroom flat with another couple so that we could keep the rent down. I was terrified of running out of money, but also knew that if things didn’t work out, I could go back to Belgium to live with my parents, which is a privilege for which I’m very grateful.

File Notes, printed matter, Camden Art Centre, on-going since 2004 with James Goggin / Practise. Photo: Edward Park

UE: Can you describe where you’re based now and what considerations you took in choosing where to establish the studio?

SDB: Right now, the studio is on the top level of our home in the centre of Ghent, Belgium. We have moved around a lot; from Bethnal Green to several studios in Dalston, then two in Clerkenwell, Liverpool, Hackney Wick, back to Dalston, and then Antwerp. Rent in London just kept going up; we were always being chased out by property developers.

Nowadays, people seem to care much less about where you’re based. I have clients all over the world, some of them I have never even met in real life. Since the climate emergency became so pressing, I have been trying to reduce plane travel, and Covid-19 has helped to make people feel at ease about meeting online.

Graphic Design: History in the Writing, co-edited by Sara De Bondt and Catherine de Smet, Occasional Papers, 2011

UE: Do you see a link between your environment and creativity? How important is the studio’s physical space?

SDB: Yes, I think it’s essential to have a good screen and a comfortable chair so you don’t get neck or back pain. It should be a warm space where you can concentrate, but also be relaxed enough to do silly things or make a mess.

UE: Can you shed some light on your working process and how you work on projects as a collaborator or a small team?

SDB: It matters to me that there is no set working process. I try to keep my practice open and moving. I didn’t realise this when I was starting out, but you can completely invent the type of studio you want to run — and it can be as weird or unconventional as you are yourself. You don’t need to conform to existing models. You don’t need to be answering the phone nine-to-five or have a flashy office in a capital city.

Right now, my practice is designing, but also teaching, doing a PhD and running a publishing company. Sometimes I will be in the playground with my kids when a client phones. It is one giant melting pot, where everything feeds of each other, and I no longer feel the need to apologise for it or pretend it isn’t.

I enjoy collaborating, so I often invite people to share projects, because it inspires me. They can be graphic designers, but just as well architects, programmers, furniture designers, typeface designers, animators or photographers. I like to brainstorm together from the beginning; I don’t believe in the mythical lone genius designer at the top.

At a certain point in London, the studio had grown to five people, but it didn’t make me happy; I spent my time organising people instead of designing. These days I try to keep it light. Sometimes I hire an assistant for production when a project requires it. In that case, the roles are clear, and I don’t feel guilty about not giving an employee enough exciting projects.

Tree of Codes, book design, Visual Editions, 2010. Photo: Edward Park

UE: How much focus do you put on administration, financial management and forward planning? Do you have outside help, an accountant, for example?

SDB: Yes, there is an accountant, but they just fill in the tax and VAT returns. I often wish I had a business partner who could just take care of that side of things for me because I hate spending time on it. It’s hard enough juggling all the other balls in my life.

I have always just rolled from one project into the next. Perhaps I should try to take matters more in hand, get a proper website, take time to think about where to go next, but there always seem to be other priorities with more fun.

UE: Is there a studio manager role? What about project management?

SDB: In London we used to have a part-time studio manager, artist Kate Morrell. At that point, there were several of us in the studio — Kate would keep the books in order and make sure we had enough studio supplies. She was also the distribution manager of [our publishing company] Occasional Papers one day a week.

It works best when designers are managing their projects themselves. Organising the schedule is part of the process: if you have a well-designed timeline and have agreed with the clients on what the steps will be, the designing itself becomes a lot easier, too. You lose information if someone else sits in between that line of communication.

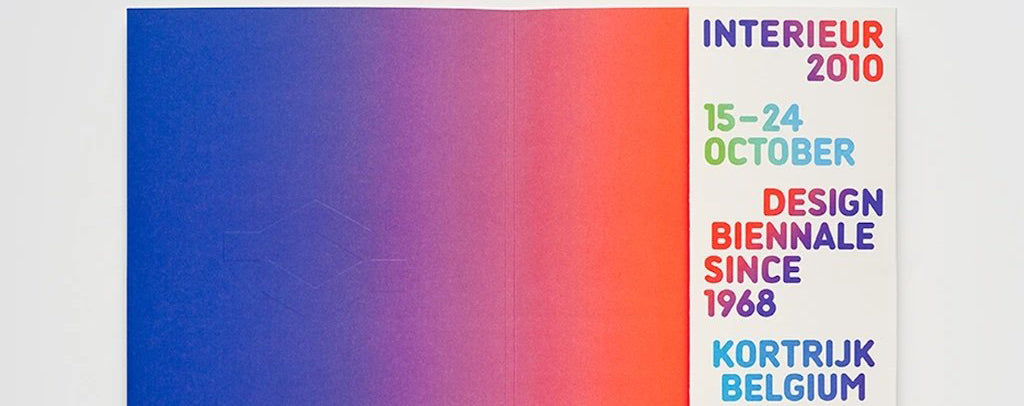

INTERIEUR 2010, press pack, Interieur Foundation, 2010 Photo: Edward Park

UE: Can you define how you balance creativity with profitability?

SDB: I’m not a hard-nosed businessperson and I think I often charge too little. We have had share agreements; it seems only fair when you’re employing people and making a profit thanks to their labour. I’ve had very talented people working for me, who have influenced the core of my practice. I’m thankful to them: Gregory Ambos, Sam Baldwin, Helios Capdevila, Mark El-khatib, Apsara Flury, Luke Gould, Piper Haywood, Sarah Horn, Thomas Humeau, Jelle Kopers, Jasmine Raznahan, Chris Svensson, Sueh Li Tan, Merel van den Berg, and many others.

At the moment, I’m doing a PhD at KASK School of Arts at Ghent University. I teach and get paid for my research time, which is enough for me to live off. That ends next year, at which point the studio will need to make more money.

UE: What about self-initiated projects — if you do them, how do they fit in with the studio’s practice? What purpose do they serve?

SDB: Making things for the sake of making them is not my cup of tea, I could never be an artist. Instead, I create structures to force myself to work outside of the traditional service-based client model; Occasional Papers, curating, teaching, the PhD research, etc.

In general, I feel that the difference between client and self-initiated work is slowly eroding, also under the influence of social media. When you see the type of projects that Nina Paim and Corinne Gisel of common-interest or Julie Peeters and Bill magazine are working on, they are all just part of one umbrella called graphic design, but clients are no longer the core of the story.

A Needle Walks into a Haystack, printed matter, Liverpool Biennial, 2014. Photo: Edward Park

UE: I’d like to ask you what the best part of running a design studio is — but first, what’s the part you like the least?

SDB: Sometimes there are days when all you get is negative feedback. Being a designer can be hardcore. You’re always putting yourself out there: asking people to give their two cents on things you’ve made for them.

UE: And the best?

SDB: Design is one of the few professions that enables you to never to stop learning: about an artist you are making a book about; a topic you are designing an exhibition for; or a furniture maker you are collaborating with. Running your studio means you are free to live how and where you want to.

UE: Finally, what advice would you give to anyone setting up a studio? What do you wish you’d known when you started out, or what would you do differently?

SDB: To go and work in several differently-sized studios to discover how they do things: how to organise files, set up a server, document work, make back-ups, organise typefaces, do invoicing, follow-up accounting, communicate with clients etc.

When I started, I had no clue about a lot of these things and wasted a lot of time and energy. Especially when the studio grew to include several people, it would have been useful to know how to work on projects as a group. Learning from others in this way would have been helpful to me.

Studio Culture Now is available to pre-order from the Unit Editions shop.